Americans have grown to realize that the confinement of 110,000 U.S. residents of Japanese descent in internment camps during World War II was one of the most shameful chapters in this nation's history.

Yet the topic remains in the shadows, an uncomfortable chapter of history that Americans know little about.

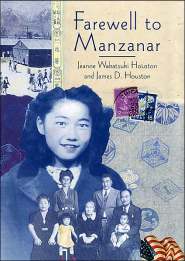

In "Farewell to Manzanar," Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston puts a human face on the episode and takes us inside one of the most famous of the internment camps. Wakatsuki lived from age 7 to 11 at Manzanar, the camp created in a bleak desert landscape in eastern California, .

While there's no justifying the internment, Wakatsuki's portrayal of life in the camp is warmer and less harsh than you often hear. These were not, she makes clear, anything like the Nazi death camps.

Wakatsuki recounts how her family, like others of Japanese descent, lived relatively unremarkable lives in Southern California before the war. But once Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the Japanese-American community immediately knew that their lives were about to change.

Forcibly relocated to Manzanar, families did their best to create a "normal" life amid cramped and drafty wooden barracks. People decorated their creaky homes the best they could, got jobs, and sent their children to school. Residents could attend church, takes classes and get items from the Sears catalog delivered.

The harm of the camp came in many, sometimes subtle, ways. Wakatsuki recalls the internment camps helped break up her family for a simple reason: They stopped eating meals together. The camps had large dining halls and in Wakatsuki's large family, the children drifted off to regularly eat dinner with their friends.

"My own family, after three years of mess hall living, collapsed as an integrated unit. Whatever dignity or feeling of filial strength we may have known before December 1941 was lost, and we did not recover it until many years after the war."

Watasuki recalls that even after leaving the internment camps, she retained a sense of shame, as if she had done something wrong. Sometimes she was excluded from a white friend's home, or from a group like the Girl Scouts simply because she was of Japanese descent.

"What is so infuriating, looking back, is how I accepted the situation," she writes. "If refused by someone's parents, I would never say, 'Go to hell!' or "I'll find other friends," or "Who wants to come to your house anyway?' I would see it as my fault, the result of my failings. I was imposing a burden on them."

"Farewell to Manzanar" is an easy and worthwhile read, bringing color and light to a period once kept in the dark.

---

(Please support this blog by clicking on an ad.)

No comments:

Post a Comment