When a flotilla of 12 U.S. Navy ships was suddenly confronted with an approaching fleet of 23 Japanese warships east of the Philippines during World War II, the situation looked bleak.

Not only were the Americans outnumbered, they were outgunned. The U.S. group was mainly smaller ships designed to support combat operations, while the Japanese had their largest battleships and most powerful cruisers.

This was the start of the "Battle off Samar," a 1944 confrontation in which five U.S. ships were sunk, seven others damaged, and over a thousand Americans died.

Yet, largely due to heroic efforts of men aboard ships the Americans called "tin cans," it ended as an improbable U.S. victory.

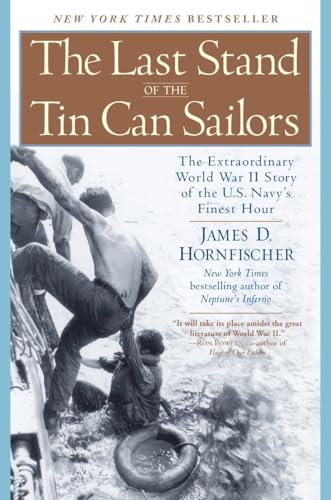

I knew almost nothing about the Battle off Samar before I started James D. Hornfisher's 2004 book "The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors." I know a lot more now, and if you like war stories, I can assure you this is a good one.

The Battle off Samar was a key part of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, a four-day clash between U.S. and Japan fleets.

The book focuses on a nearly disastrous day for the Americans. A clever Japanese ruse combined with questionable decisions by a Navy admiral left a sizable hole in the U.S. armada.

Into that gap slipped a large contingent of Japanese ships. In their path was a group of U.S. ships known as "Taffy 3" that was mostly responsible for supporting troops on land — not for fighting sea battles.

Much of the credit for the American victory, Hornfisher explains, goes to the sailors of the ships Hoel, Johnston, Heermann and Samuel B. Roberts, which made pretty much suicidal runs at the Japanese to buy time for the other U.S. ships to get further away. By the end of the battle, the Hoel, Johnston and Roberts were at the bottom of the ocean.

As a researcher, Hornfisher gets an A++. The bibliography alone is 21 (!) pages. He interviewed 52 survivors of the battles, reviewed private letters, notes and writings that family members shared with him, and assembled facts, names, figures, from copious other sources. Besides the battle itself, the author demonstrates thorough knowledge of the ships, weapons, naval training and military strategies.

"The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors" will certainly go down as the most comprehensive history of the Battle off Samar.

As a writer, Hornfisher gets a B+. The book starts slowly and at times goes into excessive detail, but it gets better as it goes on and eventually becomes a compelling page-turner.

The 130-page introductory section, while nicely setting the stage for the battle, spends too much time telling back stories of the many figures from the battle. I know Hornfisher wants to humanize the cold business of warfare, but this is not the kind of book where the reader follows a small number of characters.

There are scores of men who play key roles in the story — far too many for the reader to keep track of. Plus, the back stories are so far removed from the action in this 425-page book, it's difficult to connect a character to his later significance.

Hornfisher also sometimes uses simplistic caricatures, as when he described one sailor this way: "The boyish twenty-four-year-old with the lantern jaw and quiet manner watched over the kids on the Johnston's deck like a father. The kids who swabbed and painted and scraped and loaded supplies and took on fuel loved him like one."

But after the unhurried start, the book hits its stride. The battle chapters are exciting and vividly described.

Hornfisher's meticulousness helps fill the story with subtle details. For instance, one sailor by the name of Bob Rutter was knocked down when an enemy shell hit his ship, and he believed the sticky stuff on his face was blood and mangled flesh. "After a terrified pause, Rutter realized he was all right, and lucky too. The mess that covered him was navy beans, cooked in storage by the blast of the shell, steamed by the sudden heat, and blown through the uptake, blasting him with a blast of paste."

Another example: An enemy shell hit the destroyer Hoel's safe, which held cash to pay the crew, sent money fluttering into the air. As the author described it, "The fifty-dollar bills settled and stuck fast on the deck, the gruesome windfall drifting with the flow of blood down the bilges."

Hornfisher does not sanitize the horrors of war. He documents the brutal destruction of ships, describing men who were decapitated, had limbs blown off, or were severely burned from fire and explosions.

Still, the author should learn that not every fact needs to go into the book. The blood-and-guts scenes are so numerous they eventually become repetitive and blur together. Highlighting some key moments and summarizing others could have helped. Sometimes less is more.

The final section detailing the miseries of the surviving sailors stranded for two days in the water awaiting rescue is Hornfisher's best writing, even if the content can be painful to read. In the epilogue, he notes how Navy politics kept the heroism of the Battle off Samar from receiving much attention over the years (maybe this is one reason I knew little of this episode).

For all the death and destruction of the battle, Hornfisher eloquently describes how the ephemeral nature of naval warfare can leave little trace beyond memories:

“When a ship sinks, the battlefield goes away. Currents move, thermal layers mix, and by the time the surveyors and rescuers arrive, the water that more witness to the slaughter is nowhere to be found. The dead disappear, carried under with their ruined vehicles. No wreckage remains for tacticians to study. There are no corpses for stretcher bearers to spirit away, no remains to shovel, bad, and bury. On the sea there is no place to anchor a memorial flagpole or headstone. It is a vanishing graveyard.”