Note: This review contains spoilers!

"The Da Vinci Code" is a book overflowing with plot twists, and nearly all of them are set up smartly to deliver maximum surprise ("Why didn't I see that coming?," I wondered more than once). But one of the plot twists — the biggest, in fact — is a real head scratcher.

Near the end of the book, a character named Leigh Teabing, a wealthy religious scholar, suddenly turns against the two main characters in the book, Robert Langdon and Sophie Neveu. He pulls out a gun and orders them to help him find the Holy Grail, which in this book is described as a treasure of relics and documents related to the founding of Christianity.

But here's the thing: Robert and Sophie had been helping Teabing on the hunt for the Holy Grail. The three of them had been working together. Much of the book followed them as they tracked down clues and solve riddles scattered across France and the United Kingdom. So what was the point of suddenly using a gun to order Robert and Sophie to do what they were already doing? It just doesn't make sense.

Sure, if Teabing wanted to keep the "treasure" to himself, he might turn on his companions — but only after they'd actually found the Holy Grail.

There's a hint from author Dan Brown that Teabing was worried about the fact that his manservant, Remy, had been revealed to be a traitor. Maybe this would cause Robert and Sophie to suspect Teabing's motives, too? But that would be a weak justification for pulling the gun. Robert and Sophie, in fact, had no suspicions about Teabing, and he should have known that.

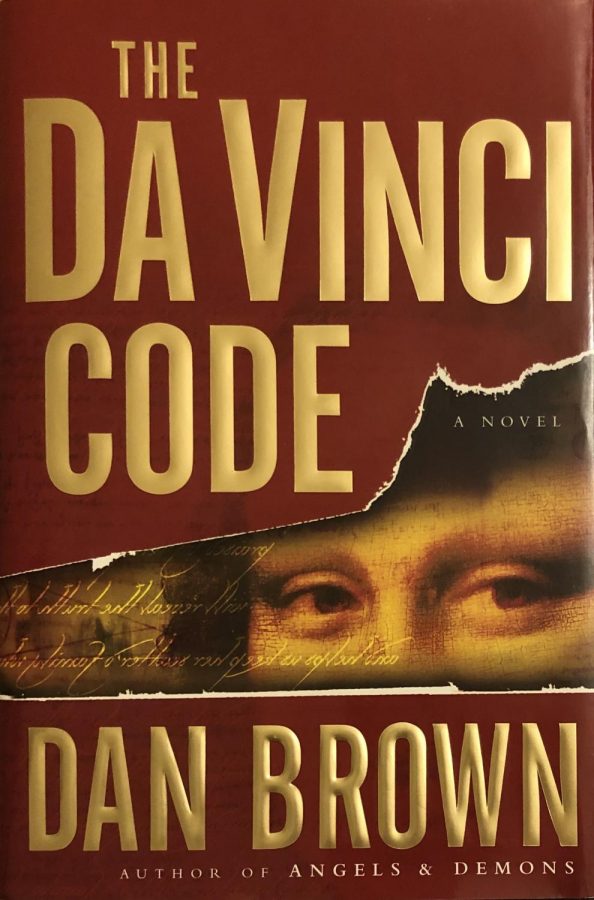

It pains me to focus on this plot flaw, because the rest of "The Da Vinci Code" is a brilliantly conceived and elaborately designed story. Brown weaves layer upon layer into the plot, vividly embellishing a tale that sprouts from a single murder into an international scheme that somehow manages to involve Jesus, Mary Magdalene, Leonardo Da Vinci, Isaac Newton, multiple popes, Francois Mitterand, the entire Catholic church and much more.

Puzzle lovers will love the story for the many coded clues that the characters must crack to keep the story moving forward.

Brown outlines a centuries-old conspiracy by the Catholic Church to support the concept of a divine Jesus, while attempting to obliterate all evidence that he was simply human. Jesus was, in Brown's telling, married to Mary Magdalene and had children, and some of his offspring live among us today. The church, according to the author, has gone to extraordinary lengths to suppress this history, as it would undermine much of the foundation of the faith.

Brown, in the opening of the book, says that it is all true. I don't know if it is, but the way he tells it, it sure seems to make sense.

Still, "The Da Vinci Code" has a plausibility problem and it has nothing to do with Brown's elaborate conspiracy theory. The problem is that Brown wants us to believe that almost all the events in the book happen in less than half a day. In fact, about 80% of the action supposedly happens within about a five-and-half-hour period.

This includes the Paris police rousing Robert in the middle of the night, bringing him to the murder scene in the Louvre where he tries to help the police crack the extensive and puzzling clues left there. Sophie, a cryptologist, enters, adds more to the discussion, tells Robert his life is danger, then sneaks away and meets him the men's room for more discussion. They start to flee the museum, but then return to sneak around looking for more clues, are almost caught by police, but cleverly get away. Robert and Sophie flee in a taxi, try to reach the U.S. embassy but find it's blocked by police, go to a train station and buy fake tickets to throw off authorities, get back in the cab, drive out of town, then change directions. Then they hijack the cab after the driver gets suspicious, drive to a Swiss bank, crack a code to get inside a vault, sneak out of the bank, fight with a bank director who points a gun at them, take an armored car, then drive to Teabing's elaborate estate.

There, they engage in long discussions about the history of the Holy Grail, which themselves would probably require two or three hours, then fight with an intruder named Silas and tie him up, flee the police by driving through the woods in the dark, go to a private airport, climb on board Teabing's private plane, and fly to England where the odyssey can continue. All, supposedly in just five and half hours.

Give me a break.

In all, there's a lot to like about this book. And two things not to like.